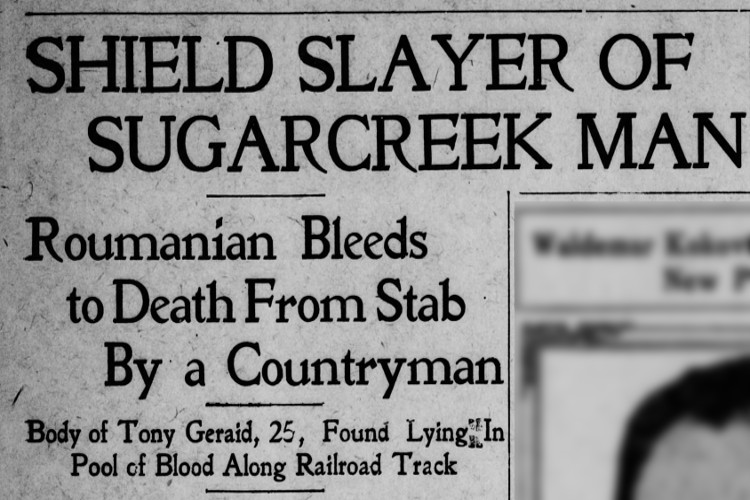

The 1911 murder of Tony Gerriod remains a mystery in Tuscarawas County history.

Tony Gerriod’s surname was spelled a number of ways in the newspaper including Geraid and Gerald. I have chosen the spelling that appeared on the only legal document associated with him, his death certificate. His nationality is also vague, sometimes reported as Italian and other times Romanian.

Tony Gerriod (1886-1911) was an Italian speaking laborer who immigrated to the United States sometime before 1911. It is highly likely he was drawn to Ohio by the promise of work on the expanding railroad network. As a single, young man, Gerriod was part of a large, transient workforce, living and traveling in close quarters with one another, where they often faced difficult and dangerous conditions. There is no evidence that he was married and he likely had limited family ties in the United States. It is probable that he sent much of the money he earned back to his family in Europe.

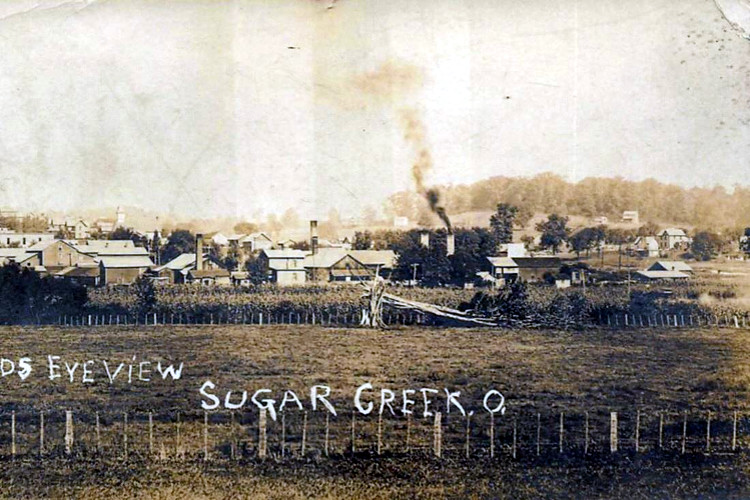

In late September 1911, Tony Gerriod’s body was found along the Wheeling & Lake Erie railroad tracks near Sugarcreek, Ohio. He had been stabbed once in the left knee, severing an artery, and bled to death. The discovery was made early in the morning by fellow workers and quickly reported to authorities. Dr. Asa E. Syler (1869-1961) confirmed the cause of death, and Sheriff John Polen (1869-1944) immediately launched an investigation. Early evidence, including Gerriod’s scattered belongings near a boxcar, suggested he had been attacked during a quarrel with fellow laborers and then thrown from the car.

Suspicion quickly fell on members of the immigrant labor gang with whom Gerriod lived and worked. Witnesses recalled that the men had engaged in a violent brawl days earlier, during which threats were made against Gerriod. Residents near the tracks, including David Shaffer (1869-?), reported hearing cries and a struggle around 2 a.m. but assumed it was another fight among the foreign workers. Sheriff Polen, however, faced resistance: the immigrant workers refused to speak, denied knowledge of the victim, or responded with evasions. Six men were arrested and questioned but later released for lack of evidence.

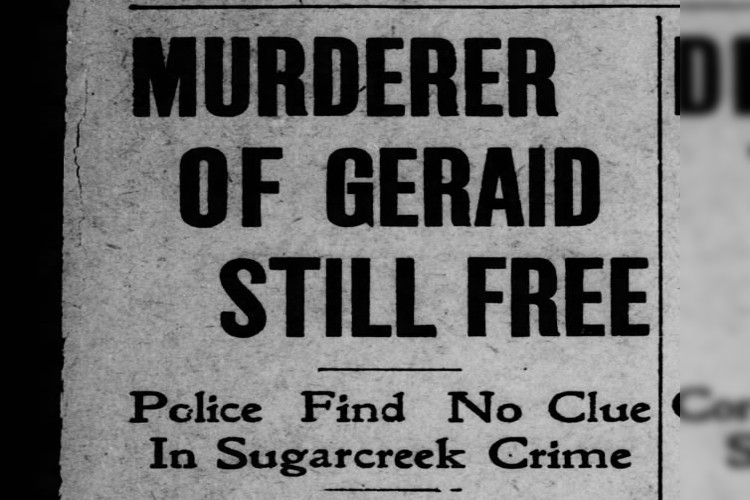

The follow-up investigation revealed additional details. Sheriff Polen learned from Norman Rohn, the American-born foreman of the work gang, that Gerriod had been drinking on the night of his death and was last seen entering the boarding car where the men lived. Authorities believed he fought with someone inside before being stabbed and ejected. Coroner Andrew W. Davis (1857-1924) examined the scene but found little useful evidence, as the laborers’ belongings had been hastily washed and cleaned, possibly to conceal traces of the crime. Davis issued a formal verdict of “murder by some unknown person or persons” and later expressed doubt that the true culprit would ever be revealed, suggesting the gang was deliberately shielding one of their own.

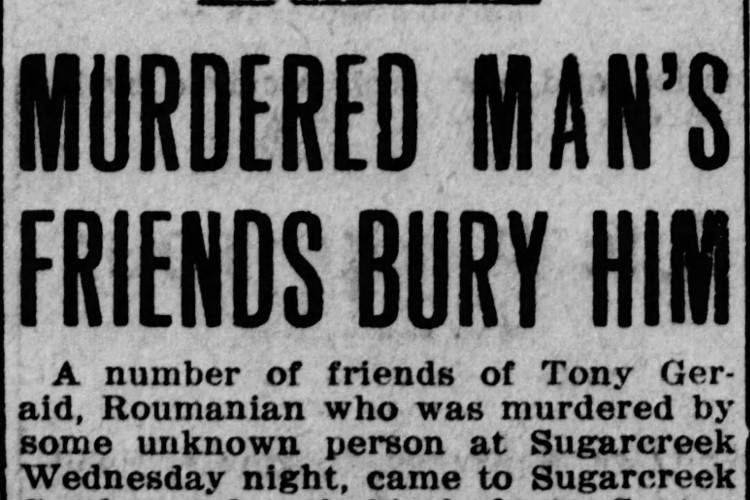

Sheriff Polen eventually admitted he had no solid leads and feared justice would never be served. The investigation was hampered not only by the silence of the foreign laborers but also by the transient nature of the work crews. Sugarcreek Marshal Homer Finzer (1882-1917) was ordered to continue surveillance in case a suspect tried to flee. Meanwhile, it was discovered that Gerriod had been connected to an Italian “secret order” in Canton, which sent representatives to claim his body. His connection to this “secret order” was likely a fraternal or mutual aid society and suggested he sought community and support among his fellow immigrants. Despite vigorous efforts, authorities conceded that the murderer of Tony Gerriod might never be identified, leaving the case unsolved.

The murder of Tony Gerriod remains a tragic and unsolved mystery, a testament to the challenges of law enforcement in a transient, multicultural society. The case highlights the dangers of life for immigrant laborers at the turn of the 20th century, where a life could be extinguished violently with little consequence or resolution. While authorities suspected one of his own countrymen was responsible, the code of silence within the labor gang and the impermanence of the work crews ultimately allowed the killer to disappear without a trace. The death of Tony Gerriod, far from his homeland, serves as a reminder of the thousands of anonymous individuals who helped build Tuscarawas County but whose stories, and fates, were lost to time.

Enjoy my stories?

© Noel B. Poirier, 2025.