A shocking discovery in a city cistern would unravel the dark, hidden chapter of young woman’s short life.

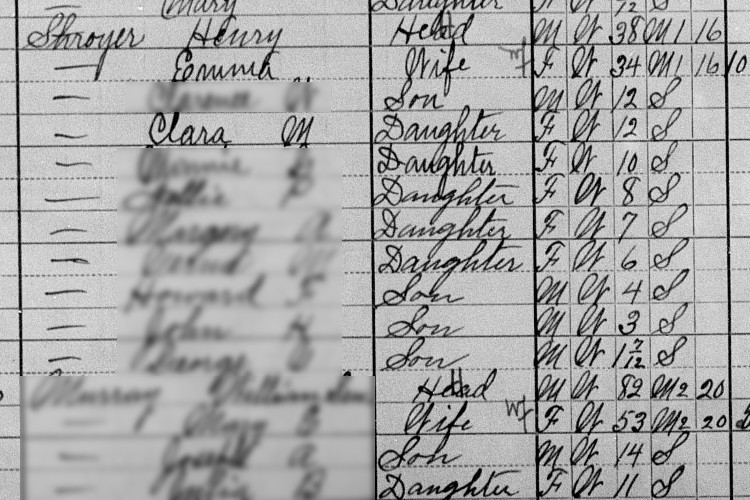

Clara Madge Shroyer (1897–1930) was born in Mineral City, Tuscarawas County, Ohio, the daughter of Henry Shroyer (1872–1930), a local farm laborer, and his wife, Selena Emma Fisher Shroyer (1876–1937). She grew up in a rural farming community as part of a large family that depended on agricultural work for their livelihood. In 1900, the census recorded Clara living with her parents and siblings in Lawrence Township, where her father worked as a farm laborer to support the household.

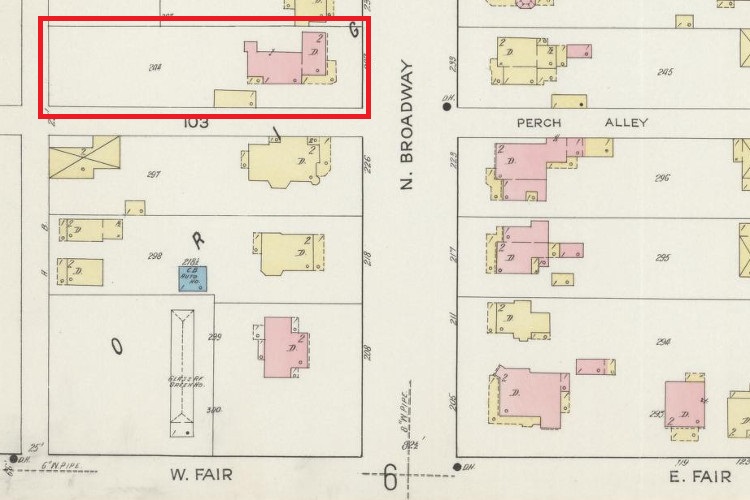

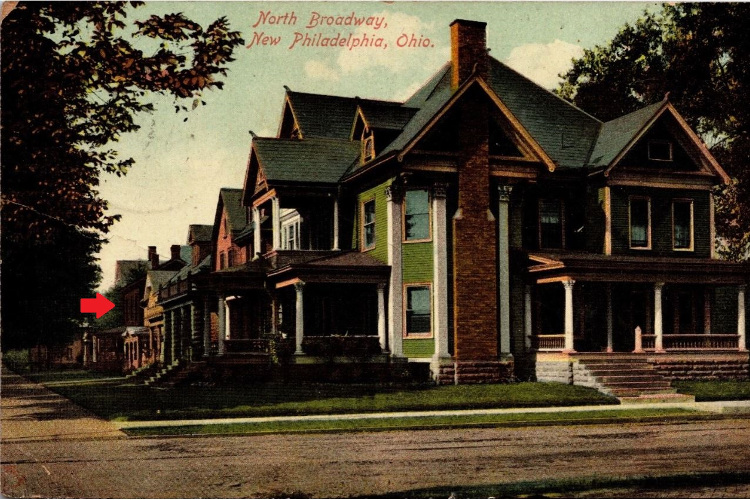

Before the 1910 census, the Shroyers returned to Sandy Township and continued their farming life. Clara, then in her early teens, helped with household duties while her father labored in the fields. As she grew older, she sought work outside the family home and found employment in domestic service. By May 1917, at the age of twenty, she was working as a live-in maid in the home of Mrs. Anna Bates (1852–1930) at 232 North Broadway in New Philadelphia, Ohio. The position placed her in a respected city household, far removed from the rural surroundings of her youth.

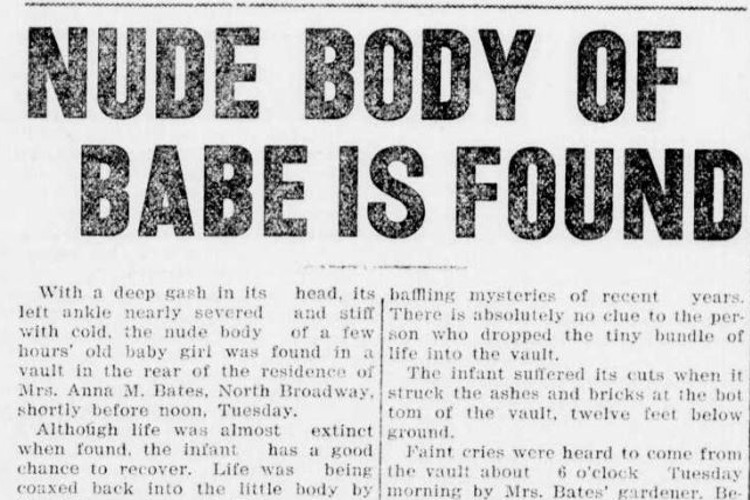

On the morning of Tuesday, May 22, 1917, the body of a newborn baby girl—only a few hours old—was found in a dry cistern behind the home of Anna Bates. Her gardener made the discovery after hearing faint cries around 8 a.m., which he initially assumed were from kittens. By 10 a.m., the cries had weakened, prompting him to investigate the cistern, where he discovered the infant. Police and two doctors were called, and together they retrieved the newborn. She had suffered a deep head wound, a nearly severed ankle, and was stiff from the cold after a twelve-foot fall onto jagged bricks and ashes.

At first, they believed her to be lifeless. Then her cries returned, and rescuers worked to warm her with hot water bottles. Within three hours she was crying vigorously, giving hope for her survival. Despite their efforts, the baby died later that day. When she was found, authorities had no leads on who had abandoned her, and physicians estimated she had been born between midnight Monday and 3 a.m. Tuesday. The investigation soon revealed the identity of her mother.

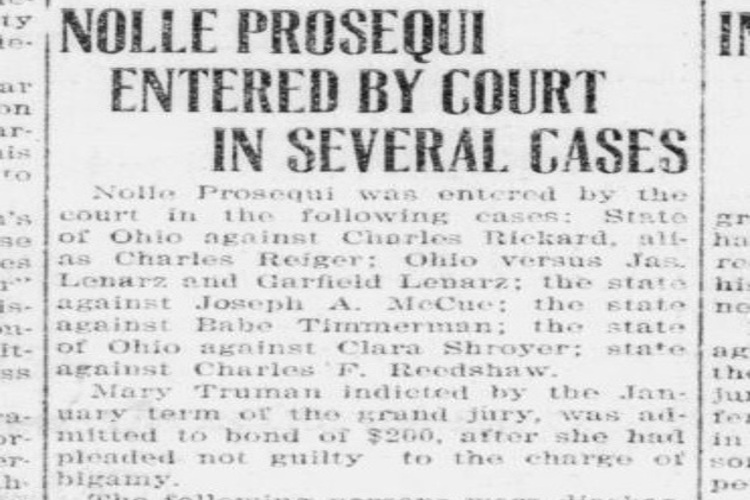

Whether Clara Shroyer’s pregnancy was known before her newborn was found in the Bates’ cistern was never reported in the press. Nevertheless, she was quickly arrested, confessed, and was charged with second-degree murder in the death of her newborn daughter. A month later, a grand jury indicted Clara for manslaughter instead—a charge to which she pleaded not guilty. Clara’s case, however, never went to trial, and in the winter of 1919 the Tuscarawas County prosecutor decided not to pursue it at all. Questions about the case of her infant daughter remained: Who was the father, and why was he never mentioned in reports? Why did it take so long to decide against prosecution? These questions will likely never be answered.

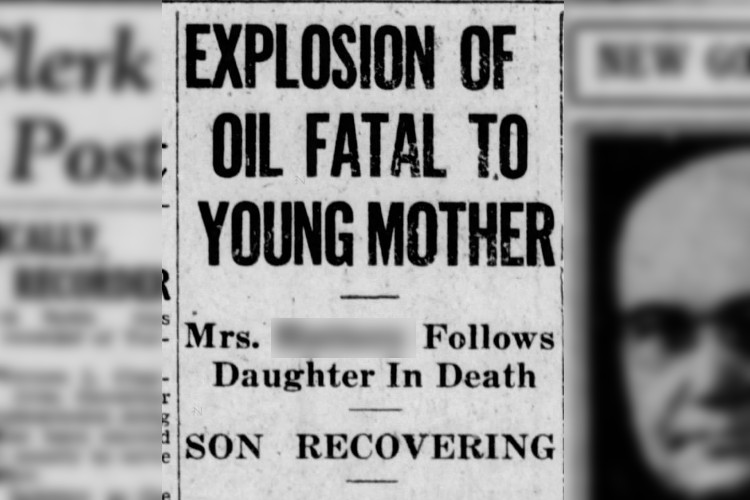

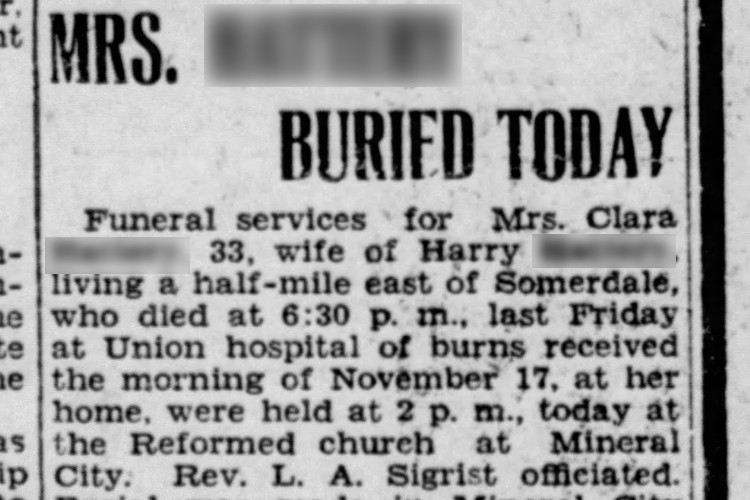

Shortly after the case was dropped, Clara married a laborer from Stark County, and the couple eventually had two children. On a cold November night in 1930, Clara attempted to light a stove in their Somerdale kitchen using kerosene. The fire quickly spread from the stove into the kitchen, severely burning Clara and her young children. Her daughter died from her burns, and Clara died a day later at the age of 33. She was buried in Mineral City Cemetery, but the burial place of her infant daughter from 1919 remains unknown.

Enjoy my stories?

© Noel B. Poirier, 2025.