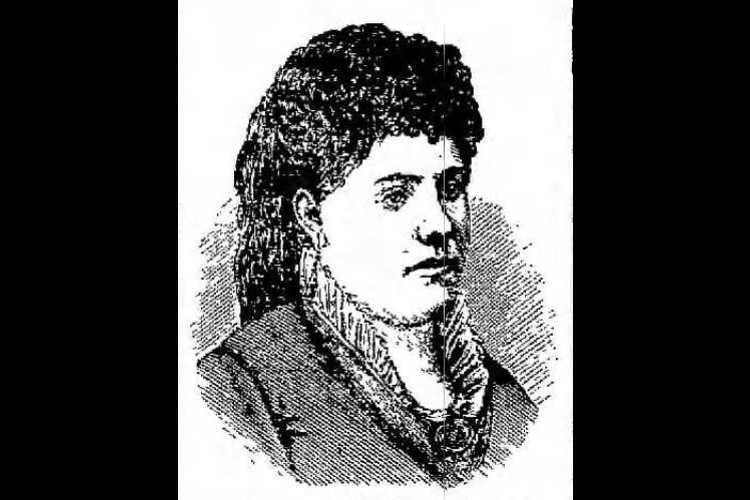

When missing Mary Senff’s body was discovered in June 1880, the attention of investigators quickly turned to the Athey and Crites families.

Note on spelling: Not surprisingly, the Senff surname is spelled differently across many of the historical documents, newspaper articles, headstones, etc. For consistency, I have decided to use the spelling that appeared on the 1850 census record for the family.

One must be careful to remember that, following a murder, the only versions of the events that took place around the murder come from those who either partook in it or investigated it. The events from the perspective of the victim are impossible to ascertain. What follows is based on the descriptions of the crime from the perpetrators and the investigation’s conclusions as they were reported in numerous newspapers at the time. Mary Senff’s version of what happened to her will forever be unknown.

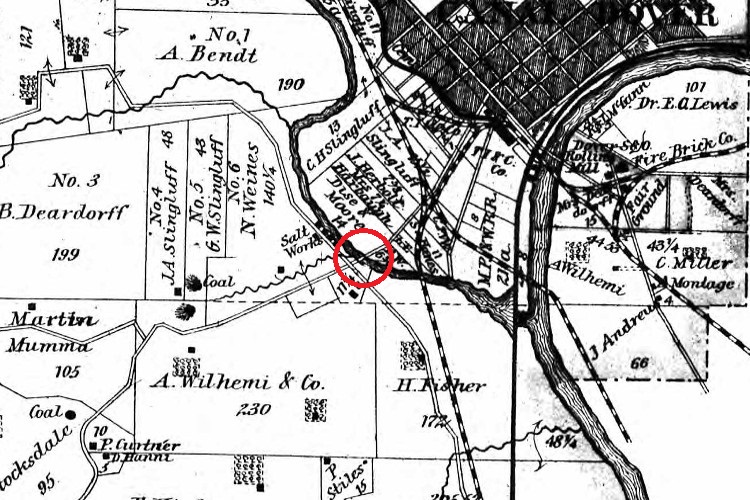

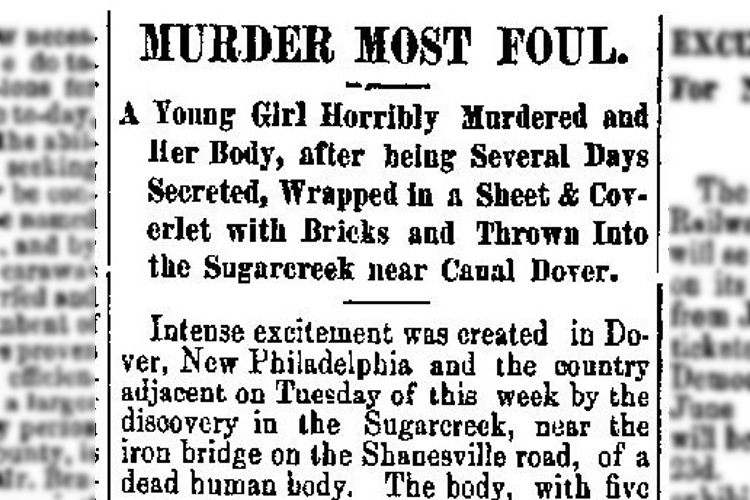

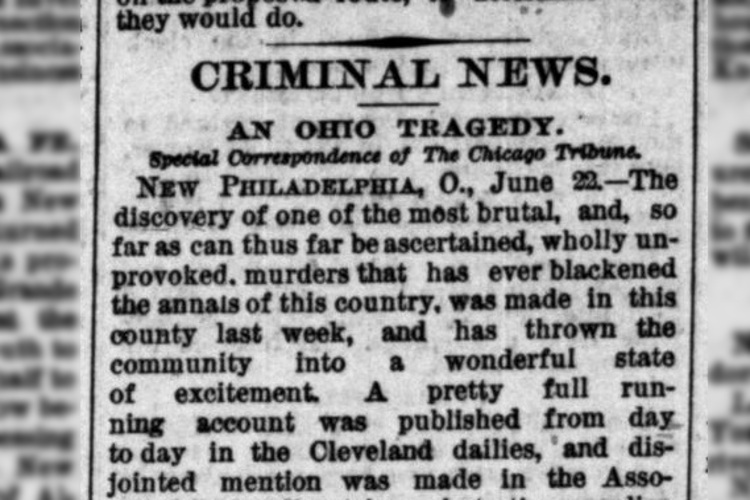

The morning of June 15, 1880, likely began like any other for the men who worked at the Salt Works along the banks of the Sugar Creek. As they made their way along the Shanesville Road west of Dover and New Philadelphia, they noticed something unusual near the iron bridge—a large, bulky mass caught against the embankment. Wrapped in a white coverlet and sewn inside a sheet, they found the remains of a woman, weighted down with bricks and covered in coal ash. Word was sent immediately to authorities, and soon, Tuscarawas County Coroner George W. Bowers (1843-1907) arrived at the scene.

Bowers’ investigation began immediately and uncovered that the woman, later identified as the young Mary Senff, had suffered multiple stab wounds, likely inflicted with a knife or an axe. Her body bore severe fractures and extensive bruising, evidence of a violent beating. Deep gashes marred her arms, clear signs that she had fought desperately for her life. The decomposition of her body suggested she had been dead for two to three weeks, yet Bowers surmised that her body had been dumped in Sugar Creek only recently. Someone had gone to great lengths to conceal her murder.

The local authorities attempted to retrace Mary’s last known movements, and they learned that she had last been seen at the Athey residence on May 29. According to Henry and Ellen Athey, Mary had departed that day, allegedly setting out for Dover in search of work. The Atheys then presented a letter, purportedly from Mary’s sister, Sarah Ressler, that stated that Mary had returned to Indiana to visit their mother. However, law enforcement quickly determined that the letter was a crude forgery, casting further suspicion on the Athey household.

The evidence mounted, and authorities began to piece together a chilling picture of what may have transpired. The extent of Mary’s injuries suggested an act of frenzied violence, one likely committed by someone with intimate access to her. The attempt to cover up her murder, the sewing of her body into a sheet, and the weighted disposal in Sugar Creek all pointed to a calculated effort to erase any trace of the crime. If her body had truly been hidden elsewhere for weeks before being dumped, then whoever killed her had been biding their time, waiting for the right moment to discard the evidence.

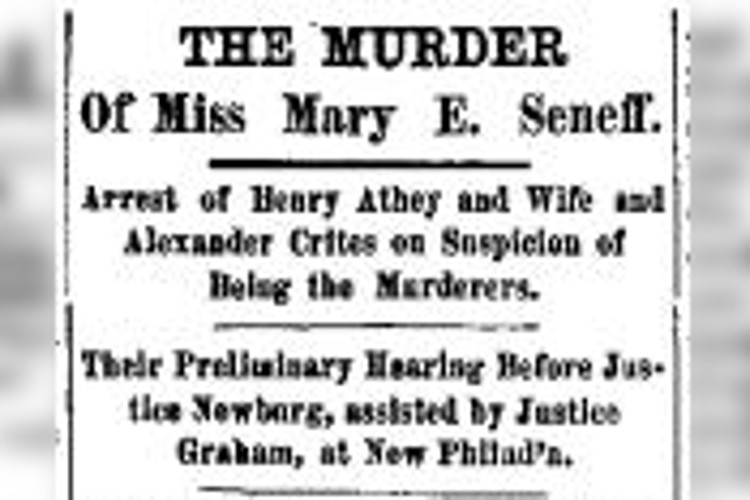

The investigation took a decisive turn when warrants were issued for Henry and Ellen Athey and Ellen’s brother Alexander Crites on suspicion of complicity in Mary’s murder. The exact nature of their involvement remained unclear, but the forged letter, the Atheys’ inconsistent statements, and their proximity to Mary’s last known whereabouts made them prime suspects. Henry and Alexander’s statements to authorities and a subsequent investigation of the Athey home shed light on Mary Senff’s last minutes alive and how her life ended at the hands of Ellen Crites Athey.

Enjoy my stories?

© Noel B. Poirier, 2024.