The construction of Jack’s House of Hope by the Friends of the Homeless of Tuscarawas County motivated me to take a look at the history of this building, discovering something innovative in its design was not expected.

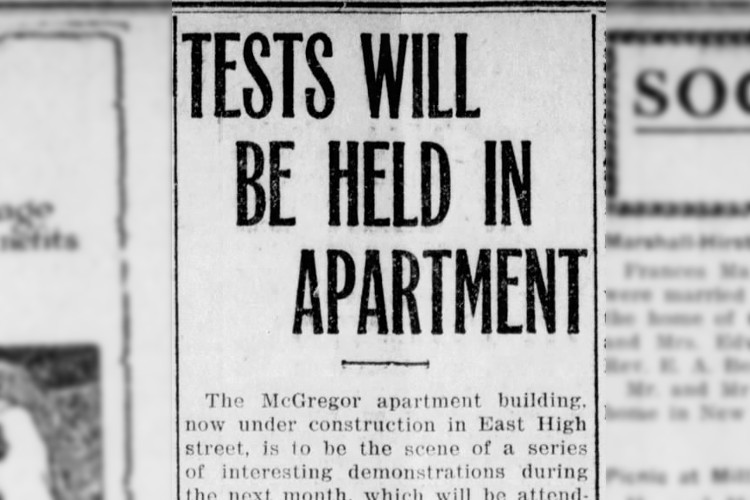

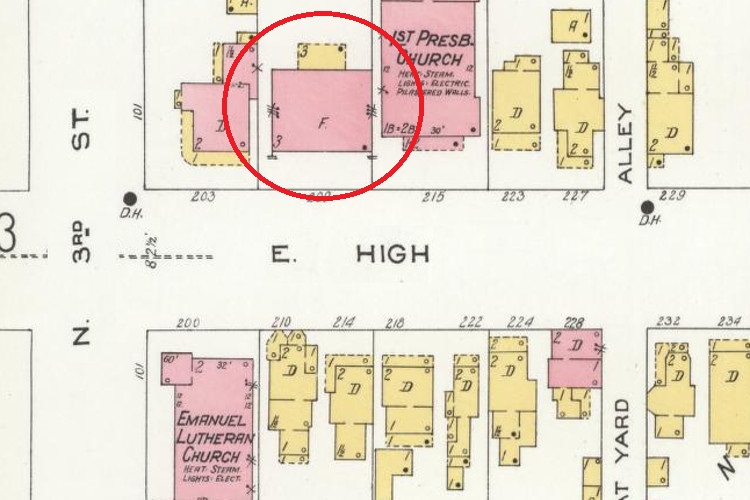

In June 1919, New Philadelphia became the site of an innovative construction experiment when the McGregor Apartment Building, then under construction on East High Street, was selected for a series of engineering demonstrations. The demonstrations, attended by engineers from Cleveland’s Building Department and the Case School of Applied Science, were arranged through a collaboration between Donald McGregor, owner of the property, and John J. Whitacre, general manager of the Whitacre-Greer Fireproofing Company. Their goal was to showcase a groundbreaking approach to building floors—the patented “Schuster System”—which promised to revolutionize fireproof and soundproof construction.

Behind that experiment was Donald McGregor (1887-1944), a man whose career carried him far beyond his hometown. A native of New Philadelphia and the son of the late Probate Judge LeRoy McGregor (1847-1912) and Nora Judy McGregor (1860-1930), Donald began his newspaper career as a reporter for New Philadelphia’s The Daily Times before joining the Cleveland Press. His talent then took him to New York, where he became a war correspondent during World War One and later served as the London and Washington representative for the New York Herald during that war. A captain and aide to the chief signal officer of the U.S. Army, McGregor also covered President Woodrow Wilson’s campaign, traveling as part of the president’s official party.

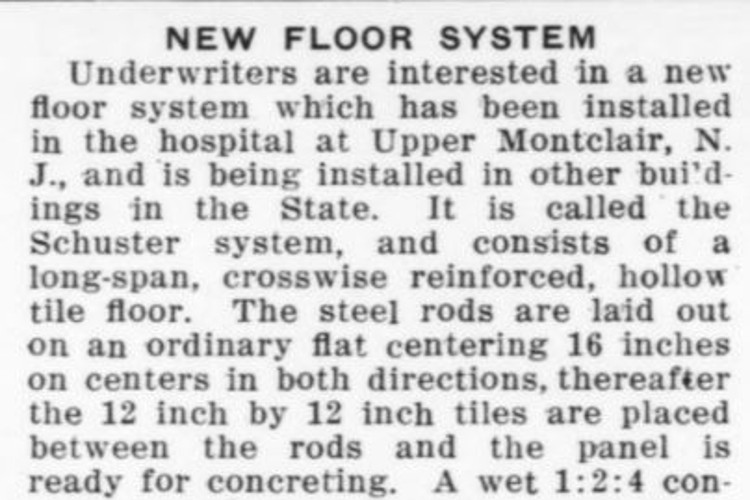

The Schuster System, developed by the Schuster Engineering Company of New York, relied on a “two-way” method of floor construction using hollow tile, concrete, and steel reinforcing rods. Builders began by erecting a wooden staging framework, carefully calculated by engineers to support the necessary pillars and beams. Steel rods were then laid across the framework in two directions, forming a grid that supported hollow tiles. Once the tiles were placed, a layer of fine concrete was poured over the surface and allowed to set, creating a rigid and durable structure. The result was a floor that could carry heavy loads, resist fire, and muffle sound far better than traditional methods.

Whitacre, a former congressman and head of one of the country’s leading fireproofing companies, viewed the project as an opportunity to introduce the Schuster System to Ohio. The Whitacre-Greer Company had secured exclusive rights to use and market the method across Ohio and neighboring states as far west as Chicago. Engineers from Cleveland and students from the Case School of Applied Science were brought in to document the process through photographs and technical notes, which were later to be compiled into a promotional booklet. The demonstrations were intended not only to highlight the efficiency and strength of the new system but also to encourage its adoption into Cleveland’s official building code.

The McGregor Apartment Building tests followed successful trials of the Schuster System in major cities such as New York, Boston, Baltimore, and Washington, D.C., where it had already gained approval for large-scale government projects like the War Risk Insurance Building. In those tests, the floors had proven strong enough to withstand the weight of piled pig iron without any sign of strain. With the 1919 demonstrations in New Philadelphia, Whitacre and his partners hoped to bring that same level of modern engineering to local construction. The project marked a forward-looking moment in Tuscarawas County’s building history—when New Philadelphia briefly stood at the forefront of American architectural innovation.

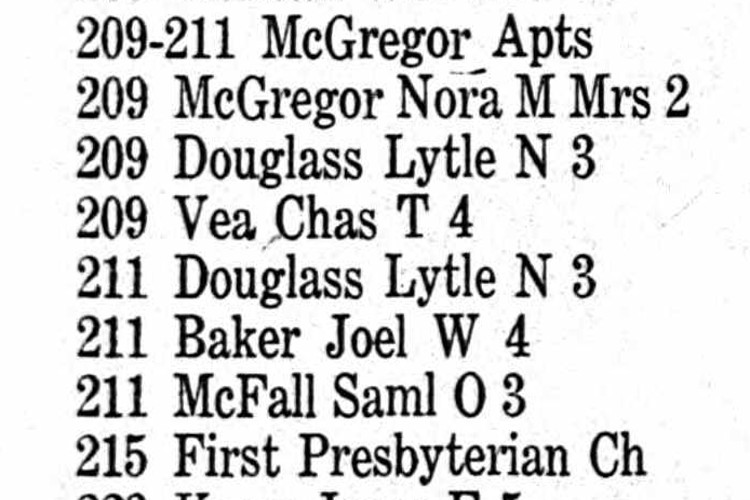

Donald McGregor never lived in the apartment building himself, but both his widowed mother and brother were recorded as tenants in the 1921 City Directory. McGregor became a respected figure in Washington, D.C., wrote for many national magazines and served as a correspondent and public relations official for the War Department. At the time of his death in 1944, he was recognized as one of the nation’s better-known magazine writers and government correspondents. Donald McGregor’s life connected his New Philadelphia enterprise with the national stage and his name remained tied both to one of New Philadelphia’s most innovative building projects and to a distinguished career in journalism.

© Noel B. Poirier, 2025.