When workers unearthed a skeleton in 1903, they exposed buried history beneath Tuscarawas County’s farmland.

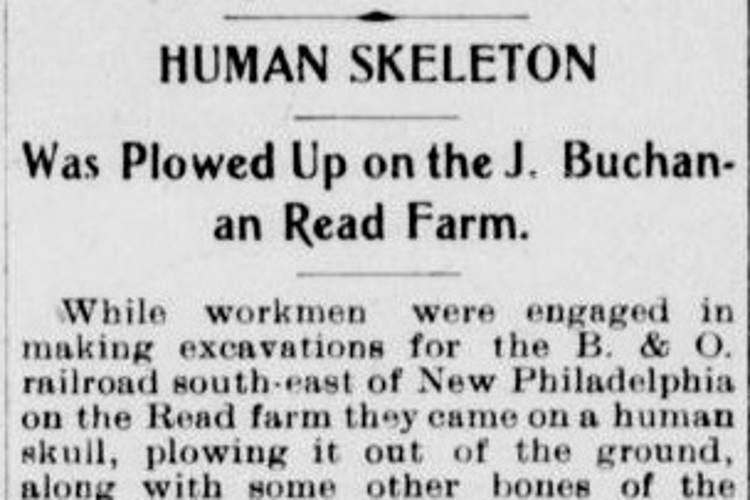

Readers of The Democrat and Times in New Philadelphia, Ohio, encountered a striking headline: “Human Skeleton Was Plowed Up on the J. Buchanan Read Farm.” in October 1903. What followed was a story that combined mystery, speculation, and a glimpse into how people of the time viewed the past and their responsibility to it. While workers were preparing ground and making repairs to the B & O Railroad tracks, they unearthed a human skull and bones, well-preserved yet clearly belonging to someone long dead.

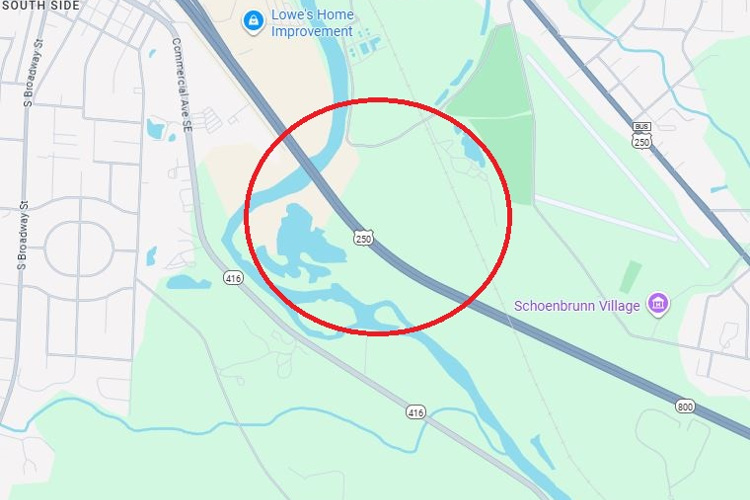

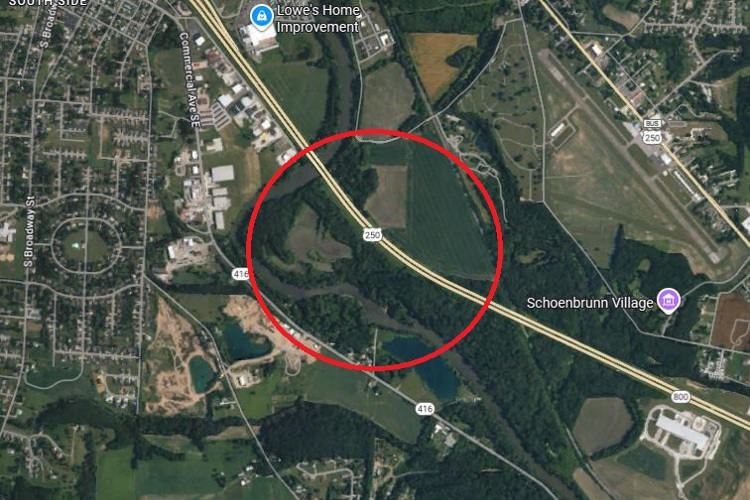

By the time the skeleton was found in 1903, the John Buchanan Read (1811-1885) farm was subdivided between two of his sons, Francis Marion Read (1853-1922) and Patrick Henry Read (1855-1921) with the B & O tracks running right through the middle of the properties. The land is bounded by the East Avenue Cemetery on the east and the Tuscarawas River on the west and just northwest of what was the Moravian mission community of Schoenbrunn. William C. Mills‘ 1914 Archaeological Atlas of Ohio, while showing indigenous mounds and villages nearby, shows nothing located on the Read property itself.

The discovery of the skeleton on the Read farm immediately stirred questions. Who had this skeleton once been? The paper described locals puzzling over whether the bones might belong to a victim of a forgotten crime, an early settler, or a Native American burial. According to the article, it was also not the first time skeletons had turned up on the Read property. Without clear answers, speculation filled the gap, fueling curiosity and giving the community a chance to revisit past tales of old tragedies. In many ways, the find served as a reminder that the history of a community often lies just beneath the surface—in this case, literally.

What is perhaps most interesting is how casually the remains were treated. The article noted that workmen divided the bones among themselves as souvenirs, and one man even attempted to sell part of the skull to New Philadelphia physician Dr. Darius Hefling (1837-1915). Today, of course, such actions would be unthinkable thanks to both legal and ethical standards related to found remains and laws like the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. But in 1903, curiosity outweighed respect for the dead. The bones were not treated as sacred or evidence, but as a curiosity.

Dr. Hefling, offered his professional opinion: the skull likely belonged to a Native American, based on his opinion of its shape and features. His comments reflect the scientific mindset of the time, when physicians often doubled as amateur anthropologists. Yet his remarks also underscore how quickly such discoveries were racialized and categorized, fitting into broader narratives about Native peoples as relics of a vanished past. For the newspaper’s audience, the idea of a nameless “Indian skull” added a further layer of intrigue and distance from the humanity of the person who had once lived.

Looking back now, the skeleton on the Read Farm tells us as much about the people who found it as it does about the person it once was. The discovery reflects early 20th-century attitudes toward history, science, and even mortality itself. Beneath the plowed fields of Tuscarawas County lay human stories long forgotten, still waiting to be uncovered. And while the true identity of the skeleton will never be known, the 1903 article ensured that, in some small way, that the person’s life and death were not entirely erased.

Enjoy my stories?

© Noel B. Poirier, 2025.