Harvey E. Decker’s life ended in mystery, his death and disputed will sparking unanswered questions.

Content warning: This post contains references to suicide. If you or someone you know has a mental illness, is struggling emotionally, or has concerns about their mental health, there are ways to get help. Click here for resources to find help for you, a friend, or a family member.

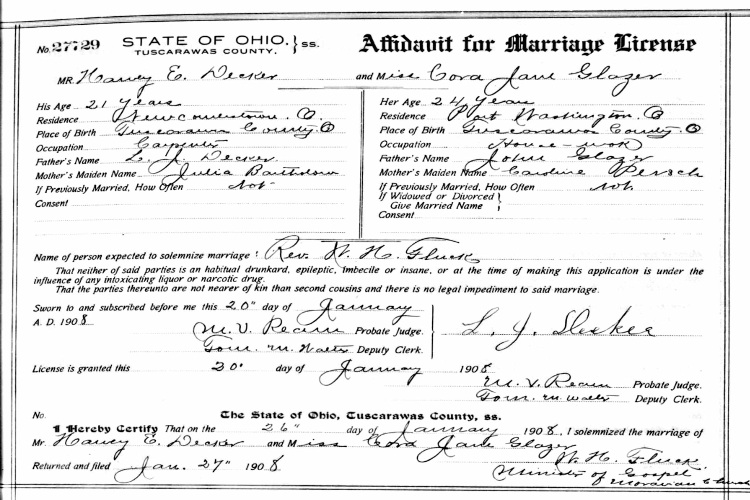

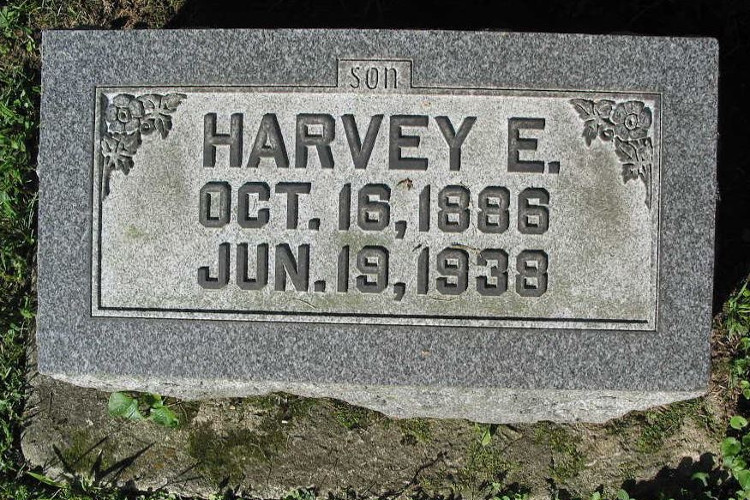

Harvey E. Decker (1886-1938) was born in Salem Township, Tuscarawas County, Ohio, the son of farmer Lewis Decker (1860-1919) and his wife, Julia Bartholow Decker (1862-1928). He grew up in a rural setting, working on the family farm and attending local schools. By the turn of the century, Harvey lived with his parents in Salem Township, experiencing the routines of farm life that shaped much of his early years. He married Cora Jane Glazier (1883-1973) in January 1908 in Tuscarawas County, marking the beginning of his adult life and family responsibilities.

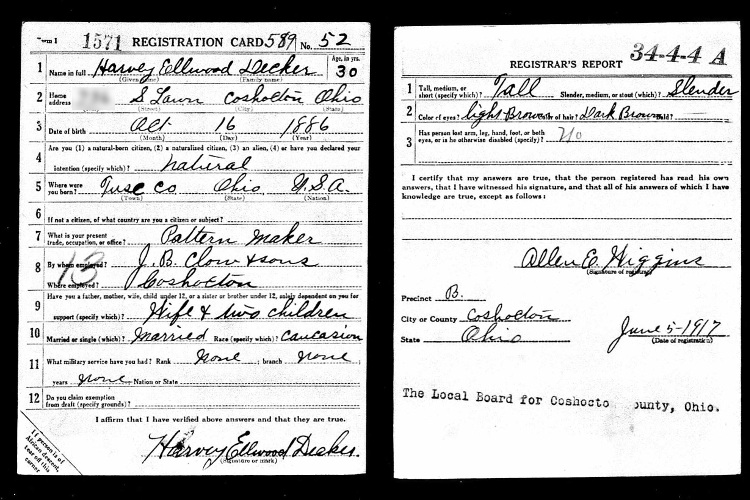

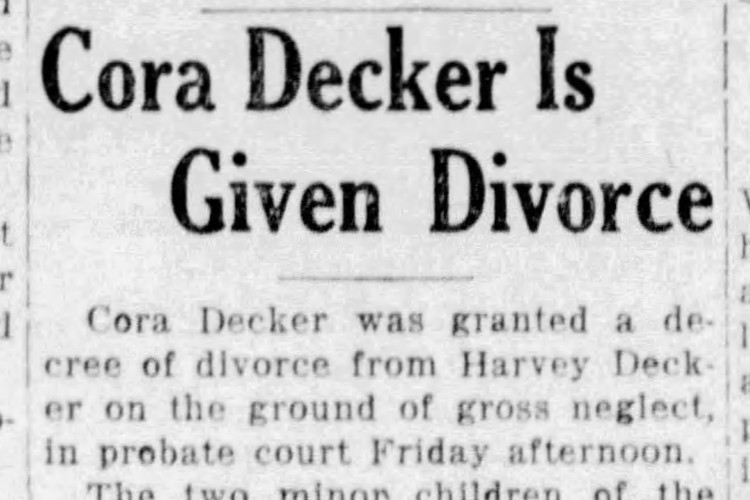

Harvey and Cora settled in Port Washington, Ohio by 1910, where he was employed as a carpenter in a pattern-making shop while raising their young child. His trade provided stability, and by 1917 the family moved to Coshocton, Ohio, where Harvey secured steady work as a pattern maker for J.B. Clow and Sons. The Deckers lived on South Lawn Street, and Harvey continued in this line of work through the early 1920s, providing for Cora and their two children. However, his marriage came to an end in 1927 when the couple divorced, leaving Cora with custody of their children while Harvey remained in Coshocton, continuing his career as a pattern maker.

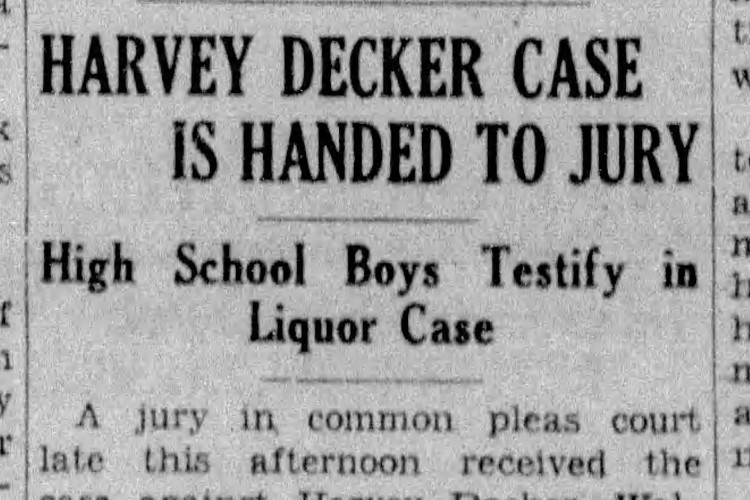

Harvey’s personal life grew more complicated in the 1930s. Living alone at first, he was fined in 1932 for possessing alcohol during a time when liquor laws were strictly enforced. He remarried before 1934, taking Susie Rehard (1886-1956) as his wife, and the couple resided together on Walnut Street in Coshocton. Despite his continued employment as a pattern maker, Harvey faced a series of legal troubles tied to alcohol possession and related charges throughout the mid-1930s, including fines and court appearances. Though he was acquitted of some charges and others were dropped after Susie plead guilty instead, the episodes reflected ongoing challenges in his later life. By 1937, further legal disputes, including contempt charges linked to Susie’s divorce attorney, underscored the turbulence that had come to mark Harvey’s story by the late 1930s.

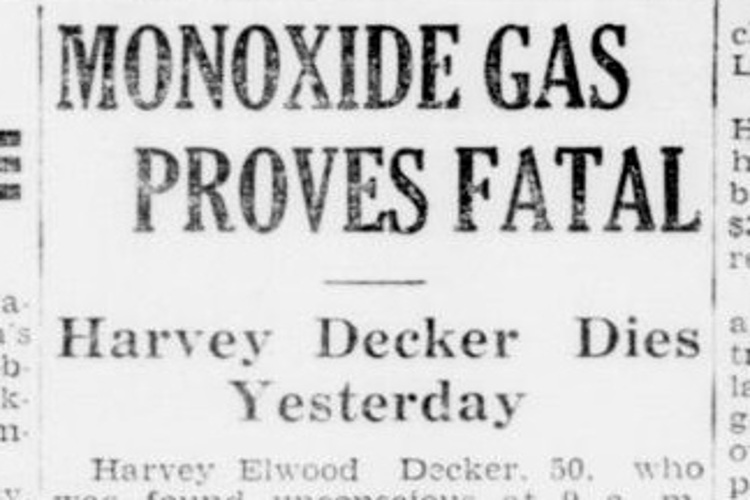

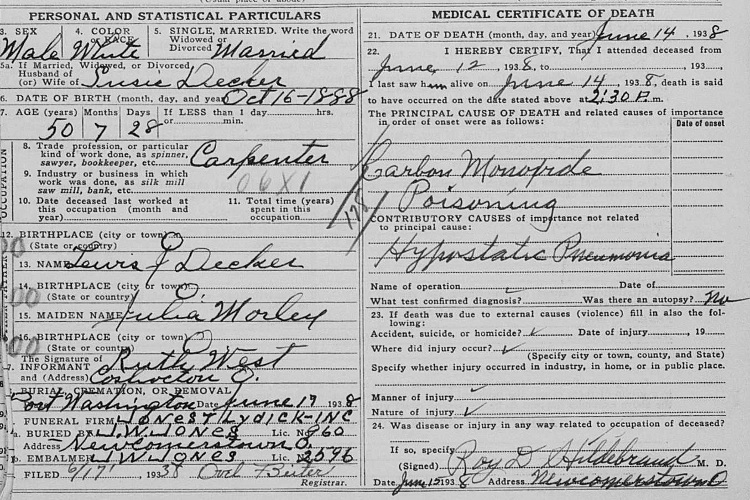

By the summer of 1938, Harvey was separated from his estranged wife and was living in a home in Newcomerstown with a housemate. Harvey now worked as a patternmaker at the Heller plant in Newcomerstown, where he worked with two men named Clarence Dawson (1897-1968) and Joe Baltrusaitis (1886-?). On June 12, 1938 Harvey was discovered by his housemate unconscious in his closed garage with the motor of his car running. Harvey, suffering from carbon monoxide poisoning, was taken to the Newcomerstown emergency hospital. He never regained consciousness and died two days later. Three days later, Harvey’s alleged will was submitted to the probate court.

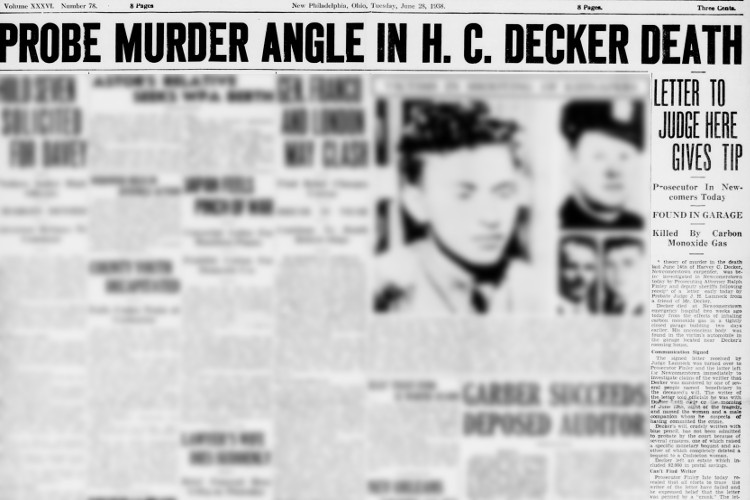

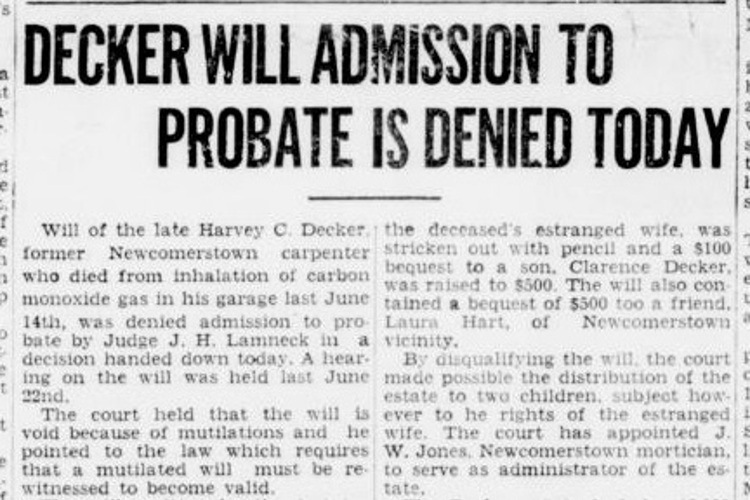

The will appeared to have been hastily drawn up and was riddled with irregularities. It left nothing to his wife Susie, and instead bequeathed his personal effects to his landlady, $500 to a Coshocton woman named Laura Hart, and $100 to Clarence Dawson, who had also signed as a witness to the questionable will. The matter grew more complicated when, on June 28, the probate judge received a letter suggesting Decker’s death might not have been accidental but could instead have been murder tied to his estate. Despite the letter, and after an investigation, authorities ultimately upheld the original ruling that his death was likely accidental carbon monoxide poisoning.

However, when the coroner filled out Harvey Decker’s death certificate he checked the box marked “accident, suicide or homicide” without noting which one. Some had noted that his previous troubles with the law and his impending divorce may have driven him to suicide. Regardless, the drama and irregularities that unfolded with Harvey’s will raised questions about Harvey’s death that were never answered publicly. On July 2, 1938 the probate court rejected the alleged will outright and later that month Decker’s estranged wife Susie, as his next of kin, was declared the rightful heir to his estate, valued at $2,751 at the time—an amount equal to over $63,000 today.

Enjoy my stories?

© Noel B. Poirier, 2025.