Fred Maurer ventured into the Arctic, and to the island on which he had previously been marooned, one last time in the fall of 1921.

Fred Maurer made the fateful decision to join a new expedition to Wrangel Island, where he had been stranded just a few years earlier. This new endeavor, again promoted by Arctic explorer and friend Vilhjalmur Stefansson, aimed to establish a permanent outpost on the island. Before setting out on this dangerous journey, Maurer married Delphine Jones in Montana. Just nine days later, on August 20, 1921 the expedition departed from Seattle, Washington, sailing north toward an uncertain fate.

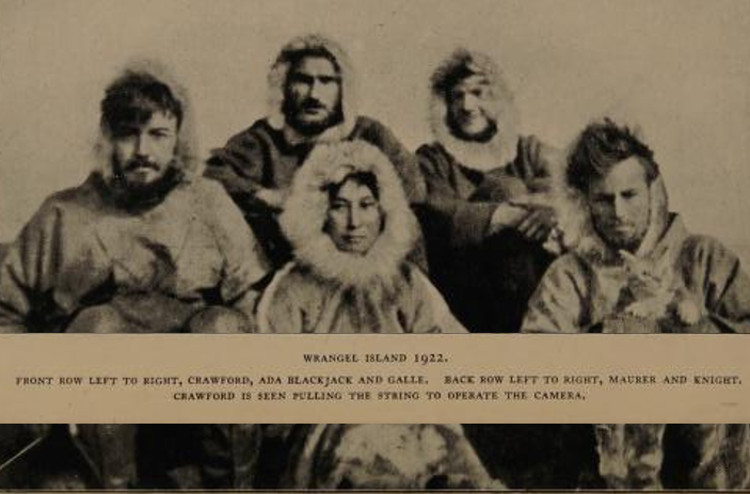

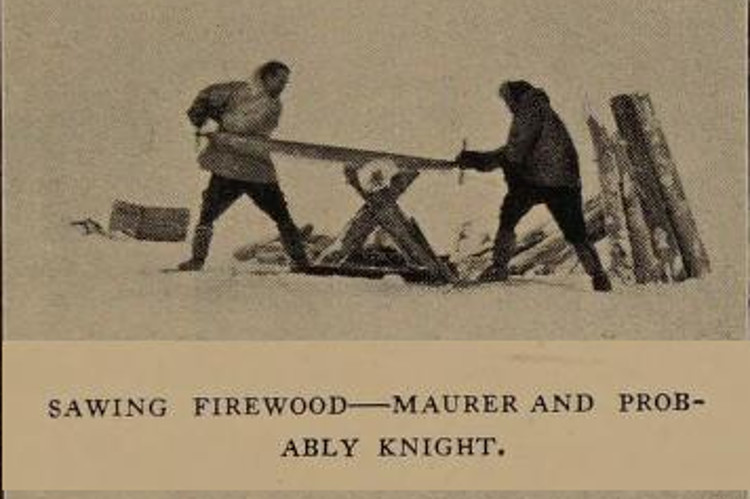

The expedition, composed of four men and one Indigenous woman, arrived at Wrangel Island in late September 1921 and established their base camp. Fred Maurer’s new efforts at Arctic exploration did not go unnoticed by his home town. A local photographer displayed pictures at his shop of Fred from his previous expedition and offered to sell prints, a sign that his journey still captured public interest. Meanwhile, back in the United States, Stefansson continued his work promoting Arctic exploration, and brought his lecture to New Philadelphia, Ohio in December 1921.

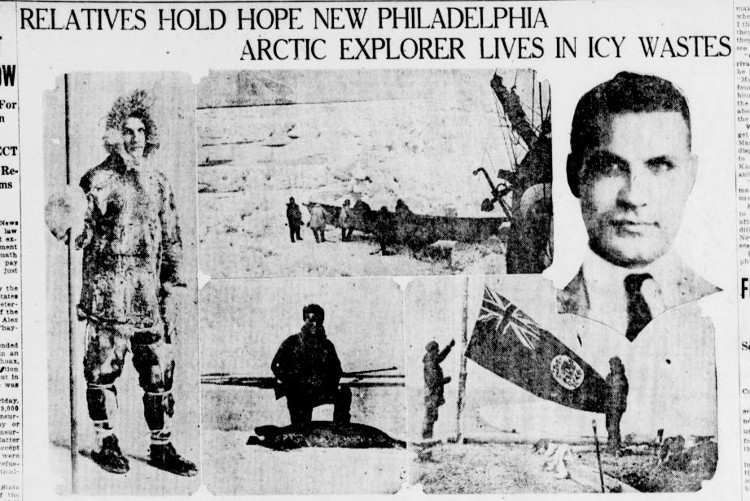

As Fred Maurer and the other Wrangel Island residents struggled through the long Arctic winter, Stefansson returned to New Philadelphia for another lecture in the spring 1922, further fueling discussions about the expedition’s progress. Around the same time, Delphine Jones Maurer, along with her parents, often visited New Philadelphia, where she sought updates on her husband’s Arctic adventure. During the summer of 1922, Stefansson himself visited the Maurer family, reassuring them with positive remarks about Fred’s resilience and abilities. A relief ship planned to visit Wrangel Island in September 1922 and, by August, there was growing anticipation that the expedition members might return soon. However, the Arctic proved unpredictable.

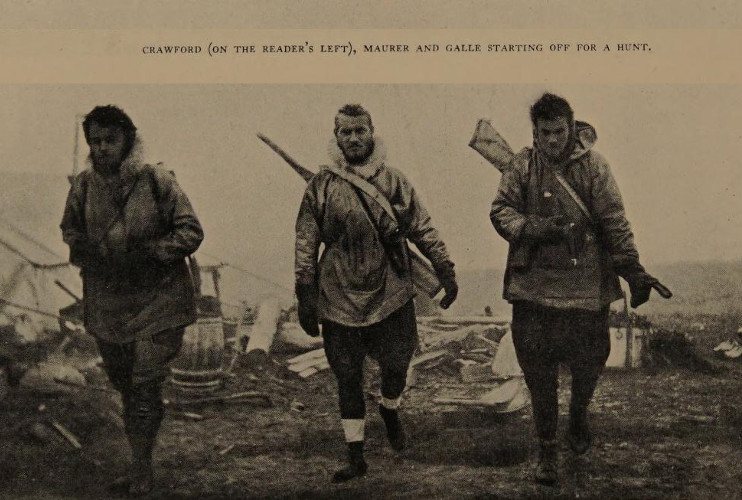

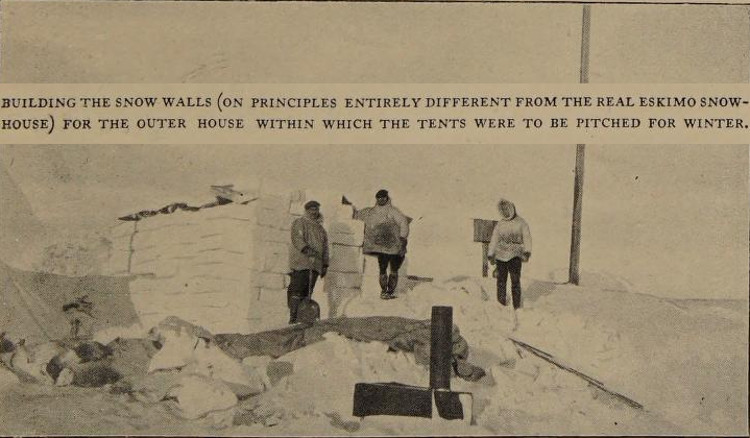

The relief ship was dispatched but heavy ice blocked its passage, leaving the team stranded for yet another brutal winter. With no immediate hope of rescue, and their leader struggling with scurvy, Maurer and the two other men of the expedition decided to take matters into their own hands. They planned to attempt a perilous journey across the ice, hoping to reach Siberia and then Alaska in a desperate bid for survival. Their plan mirrored the legendary trek of Robert Bartlett, who had led a similar successful effort after the Karluk shipwreck nearly a decade earlier.

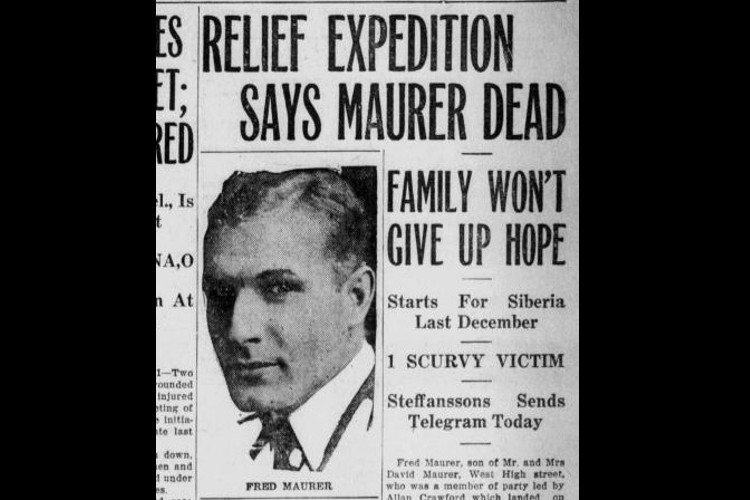

Maurer and the two other men, under a clear sky, headed south across the frozen ice field on January 28, 1923. A day later one of the worst, and protracted, storms witnessed by the two left behind on Wrangel Island began. It was unlikely that Maurer and his two companions avoided this storm and, according to Vilhjalmur Stefansson’s later assessment, they likely died as a result of falling through thin ice covered in snow or the ice flow on which they camped was turned over by the force of the winds and ice. However it happened, the men never made it to Siberia and died in their efforts to reach civilization and save their two companions on Wrangel Island. It would be months though before anyone was aware of the deaths.

Meanwhile, Wrangel Island had drawn international attention. During the summer of 1923, rumors circulated that the Soviet Union intended to seize control of the island, further complicating the unknown fate of the stranded explorers. As the months passed with no word from the expedition, hope dwindled. Finally, on September 1, 1923, a long-awaited relief expedition arrived at Wrangel Island. What they discovered was a grim scene—only one survivor remained: the Indigenous woman named Ada Blackjack. The fate of the others, including New Philadelphian Fred Maurer, now became known.

End of Part Four

Enjoy my stories?

© Noel B. Poirier, 2025.